Primary Souring to Brew Sour Beers

The discovery of five heterofermentative yeast strains that can put a bite in your beer

Heterofermentative Yeasts that make your sour beer sing (and sour)

This week, we will step away from mashing and focus on the beer brewing process. More specifically, we will look at a new methodology, suited to create sour beers, without lactic acid bacteria (LAB). Yes, it is time to update our sour beer recipe books.

While I say "new", the paper described here was published in 2017 by the group of Dr Matthew Bochman. In essence, the work reports on the identification and use of yeast strains from five distinct species, able to produce lactic acid on their own. Their discovery has opened the door to a LAB-free brew procedure, called primary souring, suited to make sour beers. Pretty cool (or sour!).

How are sours made?

Before we delve into the paper, let's first look at how typical sour beer production methodologies. We can divide existing sour beer brewing into two broad categories (see below).

The first and traditional approach is to sour your fermenting beer in barrels, using a mixed fermentation approach. Lactobacillus, present in the barrel will slowly lower the pH through the creation of lactic acid. As you can imagine, this process is time-consuming, sometimes subject to variation and requires space, skills and barrels.

The second, and a much faster approach, is a distinct souring step during or after preparing the wort. Here, brewers deliberately add LAB cultures to their wort and allow the bacteria to sour over a relatively short timeframe (24-48 hours). LAB cells are either killed off through a boil (wort) or pasteurization step. Many connoisseurs would describe these sours as "tart" and the beer profile as less complex. Some brewers add lactic acid directly to their brews and increase acidity this way.

Each methodology or process has both its advantages and drawbacks. Enter the primary souring method.

What is primary souring?

The primary souring method name exactly describes the process it denotes. This methodology consists of a single fermentation step during which ethanol and lactic acid, are produced. The application of a single step means that we don't need a separate souring stage in the brew.

How did the authors accomplish this feat?

The authors screened a vast number of yeast species for their ability to produce both lactic acid and alcohol. First, the authors went out bio-prospecting for wild yeasts. They then screened a collection of 284 strains, representing 54 species (or 26 genera), for their ability to produce alcohol and lactic acid. This work revealed isolates from five separate species that could make both compounds under brewing conditions. They are listed below:

Hanseniaspora vineae

Lachancea fermentati

Lachancea thermotolerans

Schizosaccharomyces japonicus

Wickerhamomyces anomalus

Pretty amazing.

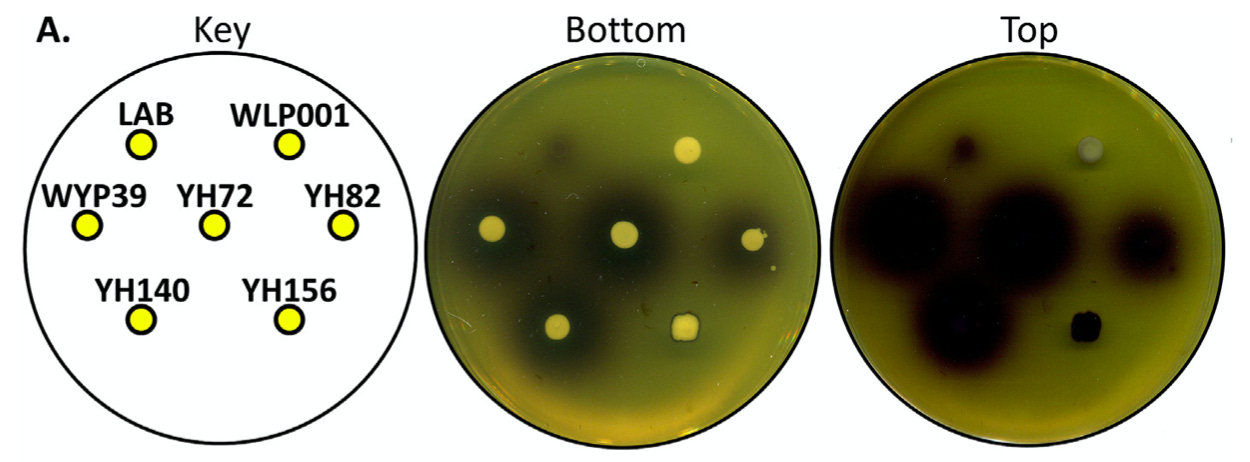

The authors used a pretty neat method to assess lactic acid production, called the LASSO assay (LASSO: Lactic Acid Specific Soft-agar Overlay). With this approach, the authors grow strains of interest on an indicator medium that turns dark brown/black in the presence of lactic acid. These halos, surrounding the yeast colonies, indicate lactic acid production and diffusion from the cells. Below you will find an example from the paper.

Are the selected yeast strains suited for beer production?

to answer that question, the authors asked ten volunteers of diverse background (and experience). Sensory analyses of beer, brewed by the laboratory, helped define the key characteristics of each strain. Interestingly and probably as expected, the beer profiles were rather diverse, ranging from tart to intensely fruity flavours, suggesting that these novel yeasts are worth considering for sour beer production.

Why is this important?

Brewers, both at home and as professionals, will always seek to innovate and make the best possible beer, using the most efficient methodologies. The availability of strains with distinct characters, suited for sour beer making, clearly allows for developing new sour beer production methods and possibly, beer styles. Notably, the authors summarised their findings and the implications nicely in the figure below.

These results also show, yet again, how bio-prospecting for yeast can help fill a void in the biochemical repertoire, available to brewers. We have to go out there and find the strains we need!

I hope you enjoyed this slightly shorter post. If you did, and you wish to have more background, please consider signing up for this newsletter or better yet, become a paid subscriber to support The Beerologist.

Cheers,

Edgar, The Beerologist.

Edgar Huitema is a Scientist, Brewer & Scientific Consultant at ExtrAnalytics. Subscribe to my free newsletter to get the latest advances in science. Contact The Beerologist at ExtrAnalytics if you wish to discuss your needs and our research.

Where can you buy these strains of yeast?