How to Diagnose Yeast and Bacterial Contamination in Your Brewed Beer

A primer on commonly used selective media to test for microbial beer contamination

Microbial contamination of beer is easy to introduce, but sometimes difficult to get rid off.

When, as a brewer, you find that your beer has gone off, you wish to know where the problem lies.

Souring beers, sulphuric smells or a lingering unpleasant aftertaste is the last thing you want to spoil your intended beer. The question then becomes, how can I determine the cause of the problem?

One way of finding out the problem, associated with beer spoilage, is to embark on microbiological testing. In this approach, you take a sample of your beer and plate it out on media that select for some bacteria or yeasts, but not others. In doing so, you can broadly define (i) whether you have contamination on your hands (well, beer really) (ii) the type of contaminant you are dealing with and (iii) the level of contamination in your beer (expressed as colony-forming units per volume of sample). Below, I will describe some common contaminants and the way we can detect them using a culturing approach (I will delve into other approaches in the future)

Do you know anyone who may benefit from this article? Feel free to share!

Common contaminants

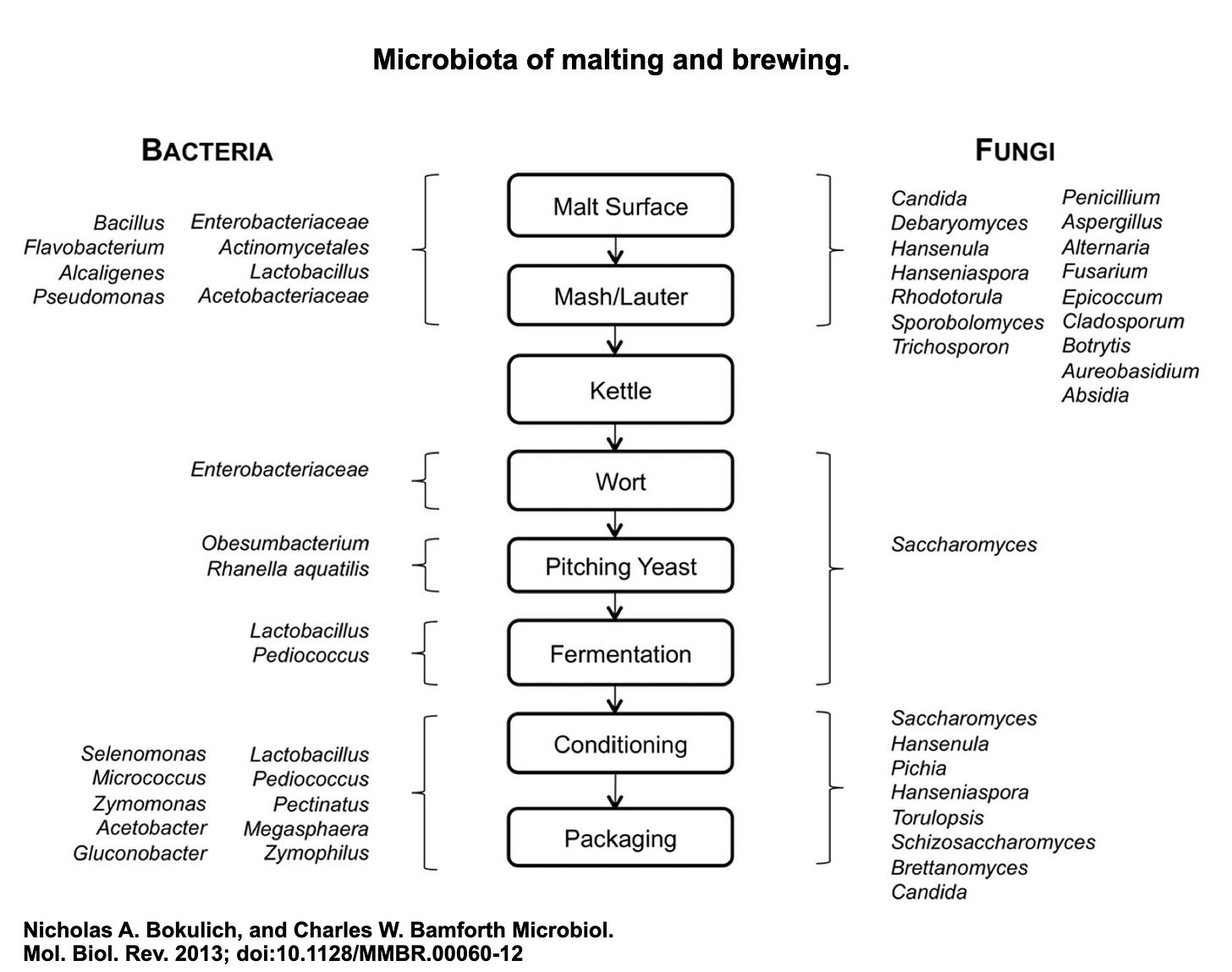

Before delving into the methods allowing the detection of microbes associated with beer spoilage, below, you can see an excellent graphical summary of contaminants from Bokulich and Bamforth (2013), commonly found throughout the brewing process. I will go a little more in-depth.

From this figure, it is quite evident that wild yeasts and some bacteria are particularly problematic in the later stages of beer production. I will therefore focus the rest of this article on their detection and identification.

Wild Yeasts

This category spans a wide range of genera such as Saccharomyces, Brettanomyces, Pichia, Schizosaccharomyces and Candida species. Notably, many wild yeasts carry genes that encode enzymes, capable of breaking down complex sugars such as starch and dextrins. In some Saccharomyces species, for example, the Sta1 gene encodes an enzyme that can hydrolyze maltotrioses. Wild yeasts, and in particular those that are diastatic, are a threat to beer production as they can grow and ferment in finished beers and impart significant off-flavours. Their detection and identification are challenging.

Selective growth: In contrast to most brew strains, Diastatic (wild) Yeasts are tolerant to copper and able to metabolize complex sugars. Both of these defining features form the basis of two selective growth strategies; one that makes use of growth media supplemented with copper and another where the growth medium only offers complex sugars (starch) as a food source. In both strategies, growth indicates the unwanted presence of yeast strains.

Another strategy relies on the use of media, where lysine is the only nitrogen source. In this media, only wild yeast strains appear able to grow, providing an alternative and complementary approach to copper-based selection.

Enterobacteriaceae or Enterobacteria

These are gram-negative bacteria. Some representatives of this class of bacteria can cause food poisoning and are associated with poor hygienic practices. Others can produce strong off-flavours and volatiles. Preventing infection by these organisms is of critical importance to all brewers.

Selective growth and identification: Enterobacteria can be grown on MacConkey Agar, which is a growth medium supplemented with crystal violet and bile salts to suppress the growth of gram-positive bacteria. Gram-negative bacteria (which comprise the Enterobacteriaceae) grow on this media, which you can supplement with additional indicative substrates such as lactose. I will not go into much detail here, this topic warrants an article on its own!

Lactobacillus & Pediococcus.

Both genera are gram-positive and considered spoilage organisms in most beers. Species within these genera are known for their ability to sour beer. While beer souring is desirable in some recipes, most brewers endeavour to keep this contaminant out of their brew setup. Both Lactobacillus and Pediococcus happily grow in the absence of oxygen but are sensitive to the anti-microbial compounds found in hops.

Selective growth: To detect either type, Hsu’s you can use Lactobacillus/Pediococcus media (HLP-Media). The advantage of this medium is that anaerobic incubation is not required, allowing culturing using relatively simple setups. You need to add Cycloheximide to this medium to prevent yeast growth. Other commonly used media used are RRLM (Raka‐Ray Lactic Acid Bacteria Medium) and BMBM (Barney‐Miller Brewery Medium). Selective growth with these media recipes requires anaerobic incubation.

Acetobacter and Gluconobacter

Both species can sour finished beer products. With the aid of oxygen, Acetobacter and Gluconobacter can produce acetic acid, which gives sour beer its flavour. Importantly, spoilage requires oxygen, which most brewers can eliminate with the proper setup.

Selective growth: Wallerstein Nutrient Agar supplemented with actidione (WLD). Derived from Wallerstein Nutrient Agar (WLN), the addition of actidione inhibits the growth of yeast and thus allows the growth of Acetobacter in the presence of oxygen. In anaerobic conditions, this media allows the growth of lactobacillus bacteria.

I hope that this primer on microbial testing was helpful. Did you learn something new? There is much more to come, just sign up here and enjoy the helpful content going your way.